art or business

It is too much even for Háry...

on view: 13. October - 12 November 2005. curator: Emese Révész, art historian

PARLIAMENT AS KNIFE-TROWING SPECTACLE The Political Cartoons of Antal Gáspár (1881-1959) and His Contemporaries

The history of political cartoons goes back to the time when the civil public as an institution was established and the ideals of the freedom of press and speech were born. Those who create them are not representatives of authority; they are advocates who speak on behalf of a free public and who, in their images, give shape to the perspective of a wider community. Their authority lies in their power to shape public opinion, as their work is reproduced in countless copies to reach thousands. They do not regard the decision makers of the community as owners of unearthly powers, but as elected representatives whose every step is watched and monitored by the public. The good political cartoon is a “time bomb,” it is an indictment with the power to expose. Through the ruthless means of satire and with a single, well-aimed image concept, it can throw light on the absurd nature of public events. It does not praise and does not deify, its language is critique. It recognises no authority and tolerates no nonsense. In Ákos Kocogh’s words: “it never speaks in run-on sentences, only in simple sentences. It chooses two points and between them the shortest distance: a straight line.” And it is for precisely this reason that representatives of authority find its straightforwardness and impartiality uncomfortable, or outright dangerous. Its cocky insolence and scoundrelous cheekiness naturally irritates the owners of political power whose agency is grounded in an unconditional respect for authority. Thus, the history of political cartoons is replete with bans and prosecutions. Their images add up to a curved mirror perspective on history, which is often light-years away from the sober accounts of history textbooks. Their satire nevertheless does not detract from their validity. Sometimes it may even seem that such caricatures are the only authentic means of reflecting on such a grotesque world. Géza Feleky expressed similar feelings in 1910: “caricature is art laughing and the art of desperation. Furthermore, on some occasions we refer to the rendering of an objective world view as caricature.” The first illustrated Hungarian humour magazine by the title Charivari was founded in 1848 by Miklós Szerelmey, who, as a typical representative of the new entrepreneur intelligentsia of the reform period, was simultaneously the artist, editor and publisher. Part of his images followed directly in the footsteps of the French Honoré Daumier, the classical pioneer figure of political satire. The war of independence provided the development of the genre with a strong impetus in Hungary. As a result of the freedom of press, illustrated, satirical leaflets flooded the country. Following this short period, public humour magazine as a genre came back to life only with the easing up of Austrian absolutism a decade later. Political consolidation subsequent to the Compromise resulted in a real effusion of such publications. In spite of the growing demand, however, there were very few artists available who were familiar with the unique genre of cartoons. As graduates of the academies of Vienna and Munich, Hungarian artists took to newspaper illustration typically at the beginning of their professional career mainly to cover living expenses. Later, a program for developing national art, provided them with much more noble and impressive challenges. Until the end of the 1870s, János Jankó was the foremost authority on political caricatures, who – turning his back on a promising career in art – dedicated himself exclusively to the ephemeral genre of cartoons. In his golden age, Jankó drew cartoons for up to half a dozen humour magazines of opposing political dispositions. Besides him, only Karel Klic and, sometime later, Atanáz Homicskó were active in the Hungarian scene. These were artists who remained loyal to the German cartoon tradition. Their compositions were characterised by a great attention to detail (with a highly nuanced depiction of clothing and the environment) whose grotesque undertones were only apparent in the characters’ abnormally large heads, exaggerated gestures and the original, gimmicky image concept. The latter usually came from the editors or readers of the magazine, whose elaborate ideas were followed by the artists to the tiniest details. Their cumbersome, picture-puzzle perspective – as it would seem to us today – was an eloquent reflection of the verbalisable image ideal of the 19th century. Antal Gáspár, who was born in 1889 in Kalocsa, knew this style of drawing well. As a child he too was first introduced to the bizarre world of caricatures through the cartoons of Borsszem Jankó, Üstökös and Bolond Istók. According to his recollections, in school he was already spending much of his time in the sluggard’s bench, where he could abandon himself to “doodling.” This “doodling” soon became a vocation. At the age of 12, he was already a member of the drawing team for Gyermekújság (Children’s Magazine) and later the reputed Kakas Márton also published his caricatures. (Albeit, Gáspár only dared take his drawing to the latter incognito, as a messenger boy). The turn of the century brought the renaissance of Hungarian cartoons with it. As of the 80s, fine artists began to turn up at the editorial offices in increasing numbers – artists who once studied at the academies of Paris and Munich, but also possessed highly refined professional skills and experience acquired in and around Europe, and who were ready to take the press empire by storm. The pioneer of humour magazines with a Western-orientation and a modern perspective was launched in 1883 by the title of Pikáns Lapok - Magyar Figaró (Magazine Piquant – The Hungarian Figaro). Adolf Fényes and Lajos Linek were among the artists working for this publication. József Faragó és Ákos Garay joined the leagues of innovators from the circle of Munich’s Hungarian artists. As was evident on the pages of the Fidibusz and Április, which were the most up-to-date satirical magazines of the 1910s, the modern secessionist and expressionist trends were gaining ground. The cartoons of Attila Sassy, Henrik Major, Mihály Bíró, Tibor Pólya, Marcell Vértes and Lipót Hermann reformed the turn-of-the-century, realist traditions in a lively and original fashion, with frank, to-the-point linear drawings and absurd image concepts.

Antal Gáspár’s born talent hardly tolerated the fetters of institutional education. He spent only a short time at the School of Applied Drawing and soon he became a much sought after cartoonist of national humour magazines such as Borsszem Jankó, Herkó Páter, Üstökös, Magyar Figaró and Mátyás Diák. In 1908, audiences were introduced to his early work in a joint exhibition with Lajos Linek and Márton Polgár (held at the Upor Coffeehouse), which, being a cartoon show, made considerable waves. World War I and the revolution were very damaging to Gáspár’s career. He spent five years at the battlefront, and then, as a left wing sympathiser, felt it was for the best to flee abroad in an effort to escape the White Terror. The Hungarian cartoon scene, on such a promising upswing at the turn of the century, was now severely decimated by emigration. Artists such as Henrik Major, Alajos Dezsõ, Leó Korber, Lipót Gedõ, Marcell Vértes and Mihály Bíró all continued their work abroad. Their graphic skills and humour made Hungarian cartoons an export item in high demand all around the world with major European and US publications lining up to have their share. Although Antal Gáspár was offered work by reputable publications from Vienna and Berlin, he was among the few who returned home with the easing of political tension. The period between the World Wars was not a good time for humour magazines. Of the well-known publications from the turn of the century none were re-launched, cartoons appeared almost exclusively in daily and weekly papers. As of 1925, Gáspár was working in Hungary again, and soon became the most popular and well-known political cartoonist. Between 1930 and 1934, he was employed by Pesti Hírlap, then was a member of the editorial staff at the Budapesti Hírlap. From 1937 until the end of the war, he once again worked for Pesti Hírlap, while his cartoons appeared on the pages of Esti Kurír, Függetlenség, Friss Újság, and Esti Újság. Since Gáspár’s caricatures were published, without exception, by metropolitan and national dailies, his humour shaped the political perception of a whole generation. Sándor Gerõ, Béla Mocsay and Zoltán Forrai were among other political cartoonists active at the time. Similarly to Gáspár’s work, the style and tone of their caricatures were temperately modern and moderately critical.

The years of adventure Gáspár was forced to spent in Western Europe had a positive effect on his style of graphics. According to the memoirs of Béla Paulini, in the first years of the century Gáspár’s images followed the Jankó-type perspective with such devotion, that many were made to think the artist who created them was but a “graphics Methuselah with a palsied hand.” Following his return, however, he had an array of fresh and modern images to show for himself: “And many years later, the nearly-all-man Gáspár gave way to a splendid, cheeky and agile lad who sprang forth like a squirrel from a hollow tree. The transformation was so one-day-to-the-next, that it appeared as if some wizard had swapped him, his hands, his heart, and even his brains. All of the sudden everything became modern, fresh and unbelievably witty.” Gáspár’s new cartoons were characterised by graceful line drawing, original spatial compositions and surreal idea associations. His exclusive authorship of both the image concepts and the striking captions was a rare phenomenon. “First I read the papers, I look for a topic, then I begin shaving. By the time I am done, the cartoon is finished too in all its detail. I just need to sit down and draw it,” revealed Gáspár to a reporter of the Est about his working method in 1934. It was Jenõ Rákosi’s assertion that he got the idea for a number of his editorials from Gáspár’s cartoons that the artist considered to be the highest degree of professional recognition. The Est reporter described the cartoonist as follows: “His clothes are well pressed like those of a ministerial adviser, he is bald as a professor and his lively and excited face, eyes and mouth resemble the features of a news reporter.” Gáspár’s appearance was indeed devoid of all scandalous trappings. He lived in seclusion in his flat overlooking the Danube, his life was dedicated to cartoon making.

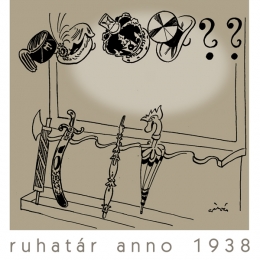

As his caricatures were mainly linked to everyday events in domestic and foreign politics, their captions often named specific participants in these arenas. His cartoons from the period between the two wars were characterised by a baroque-like crowdedness and featured quickly alternating governments, representatives and public figures engaging in the hectic skirmishes of domestic politics indecipherable to the common folk – not only in Gáspár’s renderings but in real life as well. He owed his success to his even-tempered and refined eloquence, which showed no trace of political or revolutionary anger. It was not his intention to make changes, he merely wished to reflect the absurdity of everyday politics. His approach was characterised more by indulgent humour, than by biting irony. This never hurtful, remedial tone found appreciation in a dismembered country that was trying to make a fresh start among distressing domestic and foreign conditions. “His critique is always free and independent, outspoken but never hurtful, always surprising and even if good-heartedly chiding, nevertheless, lovingly affirming too,” wrote the Budapesti Hírlap about his cartoons in 1934. Gáspár’s jokes were focused primarily on party politics, on the new program of the Bethlen era promising an economic boom, on the Károlyi Government’s lopsided welfare measures, and the disintegration of the Single Party after Gyula Gömbös’ rise to power. At times Gáspár framed his message in pertinent fine art themes, for example, by using the analogy of the Laocoon Group in reference to the complications surrounding the House of Representatives elections. In other cases, he turned puns into images, this is how the mending of a collapsing ministerial chair, the parliament as knife-throwing circus act, and the pursuit of ostrich politics gained cartoon format. In his caricatures depicting public life, empty shop shelves indicated the ripple effect of worldwide economic crisis, a robot embodied radical tax increase, and the Minister of the Interior inspected a bizarre x-ray image of the nationalistic emotions of a person who had just applied for the Hungarianisation of his name. His most time-enduring cartoons were the ones that rose above the dissensions of everyday politics and captured the zeitgeist of a calamitous era – like the image of a cloakroom from 1938 where a shako of hussars, a crane-feathered gendarme hat, a top hat and a royal crown waited patiently for their new owner. Gáspár’s work earned him extensive public recognition. In 1930 he presented his cartoons in a solo exhibition, then in 1934 a 300-piece collection was published by the title A magyar politika görbe tükre (The Curved Mirror of Hungarian Politics). In the 1940s, he frequently participated in the exhibitions of the Hungarian Association of Newspaper Cartoonists (Magyar Újságrajzoló Mûvészek Egyesülete). After 1945, as a result of his left wing affiliations, he won the confidence of the new political administration. A few years prior to the change in regime, a number of humour magazines were launched again and Gáspár proved to be an indispensable contributor to all of them. His cartoons appeared on the pages of Szabad Száj, Pesti Izé, Kossuth Népe, Hírlap, Ludas Matyi, Fûrész, Magyar Vasárnap, Képes Figyelõ, Képes Hét, Rádióélet and Irodalmi Újság. In 1950 he was the first among the cartoonists to receive the Artist of Merit distinction. During this period he was president of the Association of Hungarian Journalists (Magyar Újságírók Országos Szövetsége, MÚOSZ) a number of times. His oeuvre was exhibited in 1959, shortly before his death, at the headquarters of the Association.

Emese Révész

Bibliography •Feleky, Géza: “A nemzetközi karikatúra kiállítás.” Nyugat, 1910, I, 706-708. •N. n.: “Gáspár Antal kiállítása.” Pesti Hírlap, 10 January 1930 •N. n.: “A magyar politika görbe tükre. Bethlentõl Gömbösig.“ Az Est, 27 May 1930 •N. n.: “Karikaturakiállításra készül Gáspár Antal, aki már 12 éves koréban Gáspár apó néven illusztrálta a magaköltötte gyermekmeséket.” Esti Kurir, 10 January 1930 •Magyar rajzolómûvészek. Ed.: Imre Pérely. Könyvbarátok Szövetsége, Budapest, 1930. •A mû és alkotója, A magyar festészet és szobrászat írásban és képben. Ed.: István Csókássy. Budapest, 1933, 83-84. •Gáspár, Antal: A magyar politika görbe tükre. Budapest, 1934. •N. n.: “Gáspár Antal rajzai a Budapesti Hírlapban.” Budapesti Hírlap, 3 June 1934 •Szegi, Pál: “A karikatúra. Széljegyzet Gáspár Antal politikai karikatúráihoz. ” Fényszóró, 1945/12. •D.: “Gáspár Antal.” Világ, 27 March 1949, 4. •(szegi): “Magyar karikatúra-mûvészet.” Szabad Mûvészet, 1950, 503. •Frank, János: “A harmadik Magyar Karikatúra-kiállítás.” Szabad Mûvészet, 1951, 513-515. •Szegi, Pál: “A 3. Magyar Karikatúra-kiállítás.” Szabad Mûvészet, 1951, 546-551. •Frank, János: “A magyar politikai karikatúra. 1867-1875.” In: Magyar Mûvészettörténeti Munkaközösség Évkönyve 1951. Budapest, 1952, 90-102. •(d. m.): “Gáspár Antal emlékére.” Magyar Nemzet, 22 March 1964 •N. n.: “Kilencven éve született Gáspár Antal.” Új Tükör, 8 April 1979, 43. •Kocogh, Ákos: Vázlat a karikatúráról. TIT, Budapest, 1981. •Buzinkay, Géza: Borsszem Jankó és társai. Élclapok és karikatúrák. Corvina, Budapest, 1983. •Botos, János: A politikai humor 1945-1948. Reflektor, Budapest, 1989. •Argejó, Éva: “A politikai karikatúrák a rendszerváltás után.” Médiakutató, spring 2003, 5-19. •Takács, Róbert: “Nevelni és felkelteni a gyûlöletet. A Ludas Matyi karikatúrái az 1950-es években. ” Médiakutató, spring 2003, 45-60.