art or business

We use the best / We use the rest

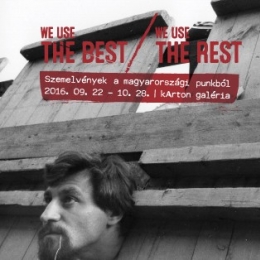

WE USE THE BEST / WE USE THE REST

Extracts from the Hungarian Punk Culture

22 September 2016 – 19 October 2016

kArton Gallery

Exhibiting and participating:

Bence Bálint, András Bánkúti, Imre Benkő, Andrea Gáldi Vinkó, Zoltán Gazsi, Ferenc Hammer, András Jeles, Gábor Klaniczay, János Kőbányai, Jenő Menyhárt, László Najmányi, Zoé Szilágyi, Tamás Szőnyei, Magdolna Oravecz, Tamás Urbán, Tibor Zátonyi, László Várhelyi, B. András Vágvölgyi, János Vető

Since the 1960’s, youth culture, the representation of young people, became a symbol for social change all around the world. In Hungary, the notion of youth culture turned out to be increasingly important and problematic in both self-definition and in culture-political debates. It was the cultural anthropological approach towards it, which questioned its previous understanding as a fixed and closed system, and its position as seconder phenomenon.

The part-liberalization of the Hungarian economy, due to its stagnation since the middle of the 1970’s, created a ‘secondary economy’, leading to many changes and to the creation of new forms in the entertainment sector as well. Studies show that these caused an even stronger opposition and polarisation between the different generations of youth cultures. The idealistic values of the beat and hippie generations were replaced by cynicism, fear, aggression and feelings of apathy. Although there was less political control over culture, the failure of the ’68 generation, the cultural vacuum and the depressing sense of timelessness led most young people to identify with the slogan, ‘No Future’. Next to drugs and alcohol it was the music which could express the generation’s ‘nihilist frustration’ as it was defined by the contemporary youth magazines. Although the system tried to domesticate these movements, by praising their ‘honest and strong’ favourites, these attempts usually remained unsuccessful. Parallel to these events another group existed with similar energy and slogans, however, originating from a different social background. Next to the movement consisting of working class youth, often growing up in state custody, the other group involved young, middle class intellectuals, artists, thinkers, musicians and filmmakers, forming an intellectual movement. While their social and existential marginality was similar, and they existed in parallel, the ‘street punk’ and ‘art punk’ scenes and actors hardly ever coincided. The only meeting (or rather starting) point was music and the philosophies surrounding it, its spontaneity, informality and accessibility. Rock was undoubtedly the crowd movement, which took fashion and body language seriously and was able to use them consciously. During this period, in the (smaller/certain segments of) visual arts, gestures, mimics, body painting, tattooing, and the exploration of identity through the body and its modification, became the centre of artistic attention. Posing general questions, such as the relationship between the body and the identity, the symbolic language of sexuality, the definition of concepts like identity, difference and the self, the understanding of self-expression and the relationship between the individual and her or his environment.

The exhibition approaches one segment of the youth culture in the period between 1978 and the middle of the 1980’s, through a collection of events, phenomena and notions. It observes the own self-creating image of the Hungarian punk subculture, as well as the way it was officially depicted, remembered historically, and categorised in cultural sociological terms.

What kind of stereotypes were created by the Ifjúsági Magazin (Youth Magazine) and other publications aimed towards young people? What creates the identity of a subculture? Was the punk movement a subculture or a counterculture? Did they have a real symbol system, codes of behaviour and their own rituals? In relation to this, what is the definition of social deviance? How do the fans of Beatrice relate to the ones of Spions? How did Gergely Molnár, Bowie and the Velvet Underground influence the body image and identity of the Hungarian neo-avant-garde? For whom did Gábor Bódy organise the 1981 film factory Makeup festival? Does it worth listening to the Cpg’s song Erdős Péter together with Ungvári Tamás by the Spions?

Next to many photos, documents, artworks, and musical documents, the exhibition is framed by intermedia artist Bálint Bence’s 2016 work, which observes the local interpretation of non-places [non-lieux], serving as a metaphor helping to understand (place) the events 40 years ago.

The exhibition is the first segment of a series, observing this phenomenon, which will be followed by other episodes (2017) and will be concluded with a collection of studies, using a wide array of both visual and textual documents.

Curator: Kata Oltai

With special thanks to:

NKA; Artpool Művészetkutató Központ, Budapest; Baksa-Soós Veronika; Magyar Fotográfiai Múzeum, Kecskemét; Országos Széchenyi Könyvtár Kézirattára, Budapest